Written by Jacob Daniel Vandor

When I was eighteen years old I traveled with my Grandfather to Austria. We spent three weeks around the Austrian border with Slovenia, visiting with old friends, meeting new people, and enjoying new experiences.

During World War II my Grandfather worked as forced laborer in a Hungarian Army Jewish labor unit. Towards the end of the war, with the Russian advancement on Germany’s eastern front, my Grandfather’s unit was transferred to the Nazi army, and moved to a small Austrian town, St. Anna am Aigen. He slaved there for the remainder of the war, digging trenches designed to stop the impending Russian tank advancement into Austria, and he would have died there as well were it not for the awesome kindness and basic humanity of the people who lived there.

There was a concentrated effort on the part of the Nazis to kill off the Jews, and my Grandfather’s group was no exception. The Nazi leaders in St. Anna am Aigen and the surrounding area were determined to starve, disease, or work my grandfather to death. And they almost succeeded. But the righteous people of St. Anna defied the draconian brown shirts, and actually made a concerted effort to feed and save the Jews. My Grandfather was one of the few Jews to survive and this is his story, the story of the righteous ones, and my story as well. In many ways St. Anna am Aigen has not really changed much in the ensuing years. But as new generations have come to leadership, a society that was repressive and sometimes even regressive concerning the Holocaust was replaced by civic leaders who were both curious and determined to find out what had happened in their hometown during World War II. This is their story, too. Their effort to try and discern what had happened in St. Anna am Aigen. They realized that if you do not understand your past, you cannot move knowingly into the future. Thanks in large part, and this is a huge understatement, to the determined and angelic efforts of Mayor Josef Weinhandl and his wife Elizabeth Weinhandl, with whom we stayed while in St. Anna, my Grandfather and I were able to meet with and interview many of the righteous people in and around St. Anna. And over a few bottles of excellent local wine and boxes of cookies, they told us their stories.

Maria Lackner is a saint, and is also personally responsible for me being alive today, perhaps more so than my father and mother. She was the righteous one who saved my Grandfather’s life. The Jewish prisoners worked in an area of St. Anna known, even to this day, as the Hölle or hell. It is a hot, and forbidding place. Maria Lackner would nevertheless make regular visits to the Holle. There was a kitchen in the Hölle to feed the Nazi soldiers in charge of the Jewish prisoners who slaved there. The food was better with more substance, with occasional meat there as opposed to the other kitchens feeding the slave laborers. The German soldiers lived in what was known as the Granite Barracks. Later, the Jews were housed there, and at the end of the war, the barracks were dynamited and burned down.

Sister Lina (Graz) was a young nun in a cloister in Vienna before the war broke out. The anti-religious Nazis quickly shut down the school and sent the nuns who were teaching packing. Sister Lina was forced to find domestic work with a family in St Anna. When the Jewish forced laborers walked past the front of her house every morning, Sister Lina would throw apples through the window towards the marching Jews. Once an SS officer caught an apple. He went into the house to investigate, but he found only a young maid polishing shoes while singing songs, busy at work. Sister Lina was warned frequently, by her friends and family, not to help the Jews because she was going to bring trouble upon herself and her family, she could be shot to death. Despite the warnings, she continued her apple crusade. One day, she invited two Jewish slave laborers inside the house and fed them bean salad. A simple kindness that showed great courage. Today, at age 87, she is still active in her mission to teach and care for a group of kindergartners.

Another story involves Maria Haarer from Waltra of the Township of St. Anna am Aigen, whose son is now a prominent member of the St. Anna community. Eight or nine Jews came begging for food at her house. A police officer arrived to conduct some business while she was slicing bread for the Jews. She was frightened to be caught red-handed and expected to be punished. But the policemen went about his business. When the policeman left he said, “I didn’t see anything.” Maria continued slicing bread to feed the starving Jews.

Ferdinand Legenstein from Sichauf (Township of St. Anna/Aigen), another prominent community member, told me stories from when he was 11 years old. He remembers that every time his mother went to St. Anna, she always carried one or two loaves of bread under her arm with her for the Jews.

Frieda Neubauer from Risola (Township of St. Anna/Aigen), can still feel the aches from working in the trenches. Three weeks on, one week off. She had to provide her own food while working, did not receive food or help or even the basic tools to dig with. Yet, in the midst of war, in the face of hardship she still regularly deposited small food packages at the panzergraben for the Jews.

On certain days Mrs. Neubauer had to show herself in one barrack at the Hölle to update her workbook of the hours she worked at the fortification job. On one of those visits she noticed something behind the barrack. Many human corpses were stacked up in a pile, including some people still alive. The whole pile of bodies were buried in a mass grave near Deutsch-Haseldorf. Later and in the days that followed, she visited the mass grave and the earth was still moving.

Imre Weisz. After coming home from the ceremony to dedicate the Memorial for Peace Monument in St. Anna, I received a call. The man on the other end of the line spoke with the same heavy accent as my Grandfather. He asked for “Sandor Vandor, Sandor Vandor” so I gave him my Grandfather’s cell phone number and thought nothing of it. I later learned that this man was Imre Weisz, another former slave laborer, who also received life-sustaining food from the villagers near St. Anna. He was born in 1928 in Mezötúr, Hungary.

Together with his family, during the sweltering summer of 1944, he was moved from Mezötúr to the ghetto of Szolnok and from Szolnok to Austria. They were forced to work in a factory on the outskirts of Vienna. He was later moved to St. Anna am Aigen. He was housed in the school building on the upper floor. Two levels of bunk bed were built in, the men packed in like sardines in a can. He vividly remembers the stairs to go up and down to and from the room, a challenge everyday.

In the mornings they left the school compound for the work site, walking past the steps at the side of the church. They were working on digging trenches (not the panzergraben but schutzengraben). For their group of ten the daily quota was to create 35 cubic meters of trench space. They were served a midday meal and there was more solid substance in their meals. Often times they would have finished the quota for the day, however they slowed down to be present when the meal was served very late in the day. After some time being treated as less than human, you do what you can to survive, even if that means actually working longer. Besides the trenches they were also forced to work on other fortification jobs.

Even with more meals served than my grandfather’s group, Weisz was still hungry and very much in need of food to supplement his meager diet. He, like my grandfather, also visited neighboring villages to beg for food. He often received apples. Many times, the apple came with an apology from the kind-hearted villager, saddened that they didn’t have enough to feed themselves and this was all they could do.

To this day he remembers the names of some of his comrades; also the SA supervisor’s name was Wagner, a name burned into his consciousness.

During their time in St. Anna, they were moved from the school building to a spot outside the village, into an unfinished wooden barrack with just a tent as cover. This happened in late February or early March because he remembers that snow covered the grounds.

While they were housed in the tented barrack, a few people, members of one family, escaped from the barracks. For collective punishment, the Nazis shot ten of the oldest members of their company. (Mr. Schober noted this episode in the Foreword 3.)

These Jews were moved from St. Anna to Mauthausen in a death march in late March of 1945, ahead of the approaching Russian army.

Imre Weisz was later liberated from Mauthausen. He provided eyewitness testimony to Dr.Eleonore Lappin who is the foremost historian on the subject of Jewish life in Austria.

St. Anna is sometimes known as the “Styrian Bethlehem”. Styria is the state in Austria where St. Anna is but the reference has nothing to do with a newborn baby and wise men. Rather, an amazingly disproportionate number of St. Anna’s children grow up to become clergy. (As of today’s count: 36 priests, numerous nuns and religious educators.) Simply put, people of god, of love, of the good way, are born and raised there. It is a simple, beautiful place, with primeval forests that smell of antiquity. It is an ancient land; one can feel history in the dirt of St. Anna’s tilled fields. And as long as people have lived in St. Anna, in this Bethlehem of Austria, they have lived by the book, and always will.

The Wurzinger family from Aigen (Township of St. Anna am Aigen.) Mayor Josef Weinhandl asked the Wurzinger family for permission to build the Memorial for Peace Monument on their field. They gave their consent quickly. For them it is very important that those events should not be forgotten. Also, that field is very suitable for the memorial because the road that is slicing through the land is one that people frequently pass by. Another reason the Wurzingers agreed was that the family was eager to support the young people’s project. It is notable that six of the St Annian students who volunteered to build the Memorial for Peace came from Mrs. Gabriella Wurzinger’s class at the Schloss Stein School of Fehring. Since the project’s completion, Mr. Andreas Wurzinger told Elisabeth Weinhandl that he often works in the fields in that area and that he has noticed that many people are visiting the Memorial for Peace Monument.

To conclude, let me introduce one of the glass tablets of the Memorial for Peace Monument (Photo and English translation).

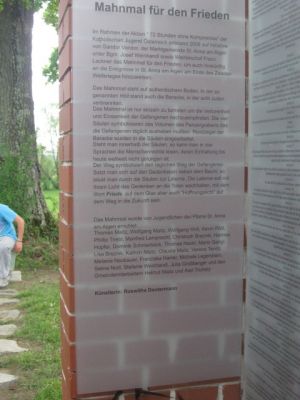

Memorial for Peace

8. “Mahnmal für den Frieden” glass tablet

In 2008, the Catholic Youth of Austria performed the “72 Hours Without Compromise” project. Initiated by Sandor Vandor, the community of St. Anna am Aigen headed by Mayor Josef Weinhandl, as well as Auxiliary Bishop Dr. Franz Lackner, the Memorial for Peace was constructed to commemorate events in Sankt Anna am Aigen at the final phase of World War II.

The monument is built in an area called “Hell,” on the actual ground where barracks stood during the war in which eight Jewish people were burned.

You can enter the monument only singularly by yourself to emphasize the prisoner’s forsaken and forlorn conditions. Four columns symbolize the volume of the tank ditch the prisoners had to dig out daily. Old bricks from the barracks were built in the columns.

Standing within the columns, one can read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in four different languages, even though as of this day the observance of these rights is not universal.

The path leading up to the monument symbolizes the daily walk of the prisoners. Sitting on the commemorative stone next to the tree, one can look through the columns to the lantern. With its light, it should bear in remembrance of the dead, but with the word “Peace“ on the glass it should also be a “Light of Aspiration“ on the way into the future.

The monument was built by the youth of the rectorate of St. Anna am Aigen:

Thomas Maitz, Gerhard Schuster, Wolfgang Maitz, Wolfgang Hirtl, Kevin Pöltl, Philipp Triebl, Manfred Lamprecht, Christoph Breznik, Hannes Hopfer, Dominik Schmerböck, Thomas Hackl, Mario Gangl, Lisa Breznik, Kathrin Maitz, Claudia Maitz, Verena Penitz, Melanie Neubauer, Franziska Haarer, Michele Legenstein, Selina Nistl, Stefanie Weinhandl, Julia Großberger and the community workers Helmut Maitz, Josef Sorger and Karl Truhetz.

Artist: Roswitha Dautermann